By Rubén M. Perina, PhD

The Organization of American States (OAS) will elect or re-elect its Secretary General on March 20 of this year. As its member states consider their choice, they will have to take into account the new reality of the Organization.

Since its inception (1948), the OAS has been the main and indispensable inter-American forum for cooperation among its member states. In its first 40 years, its main concern was security, peace and socio-economic development in the hemisphere. Today its focus is different:

1. By 1985, the majority of its members returned to democratic governance and reformed the OAS Charter to establish as one of its main purposes the promotion and defense of representative democracy. Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Uruguay led the process; Mexico accompanied it reluctantly; the US opposed it at first, but in the 1990s it enthusiastically supported it. Using diplomatic instruments adopted for that very purpose, such as Resolution 1080 “Representative Democracy” (1991) and then the Inter-American Democratic Charter (2001), the Organization helped revert coups d’etat in Haiti, Peru, Guatemala or prevent them in Paraguay, Nicaragua, Ecuador and Bolivia. In 2009, it suspended the Honduran government that took power after a coup.

2. That experience marked a paradigm shift in inter-American relations in favor of the pro-democracy principle, understood as a collective attitude and commitment to non-indifference to transgressions against democracy and to solidarity and engagement in its defense. Thus, the OAS has ceased to be a forum for dealing only with matters of cooperation or conflict between Member States, to be one where domestic matters of its members are also considered, particularly when it comes to protecting democracy and human rights.

3. The sacrosanct principle of non-intervention has lost its absolute supremacy. By committing themselves to exercising and defending democracy and respecting human rights, member states inevitably have ceded degrees of absolute sovereignty and cannot invoke the principle to conceal their transgressions. There is no longer silence or indifference when transgressions do occur.

4. In recent years, sessions of the OAS Permanent Council have dealt with the internal political situation of Venezuela, Nicaragua and Bolivia, without the consent of their respective governments, and despite their objection and that of other members who reject this new multilateral practice.

5. Recently, the Organization has had a more autonomous or independent Secretary-General (Luis Almagro) with more political prominence than its predecessors. For his admirers, his reports on the Chavista/Maduro’s tyranny and its subsequent humanitarian tragedy have forced member States to finally focus on the Venezuelan situation. Almagro has denounced Maduro’s legitimacy and has recognized the President of the National Assembly, Juan Guaidó, as president (i) of Venezuela. For those who agreed with his conduct (Venezuelan exiles and the US, Colombian and Ecuadorian governments, which have proposed his re-election), Almagro is a champion of democracy, and one who has elevated the OAS relevance in the hemisphere.

For his detractors, Almagro is a kind of “Lone Ranger” that has overstepped his role and has ignored the member states, as he does not consult them nor seeks consensus for a mandate that would allow him to act on behalf of the Organization in times of crisis. For them, his reports and public pronouncements condemning Maduro have disqualified him as an impartial facilitator of negotiations between the regime and the opposition; and in fact have not succeeded in achieving his downfall, but instead it has produced his withdrawal from the OAS. Nor has his contradictory behaviour in Bolivia gone unnoticed, first supporting the re-election of Evo Morales and then accusing him of attempting a coup via fraudulent elections in October of 2019.

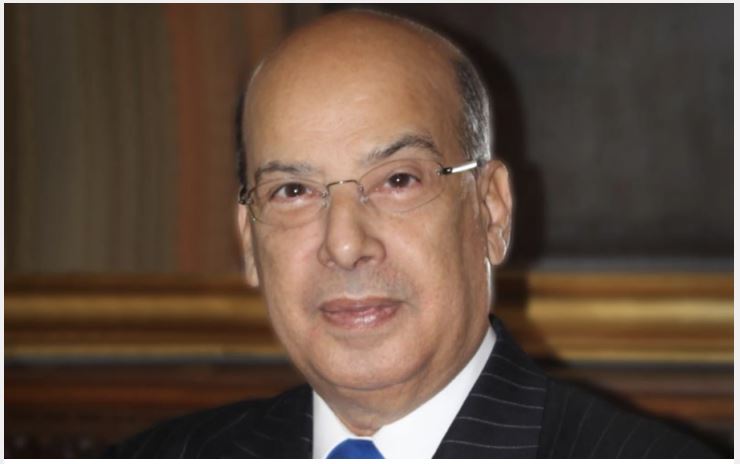

6. Several countries have criticized his conduct and do not support his re-election bid, including the outgoing government of his country, Uruguay. Antigua and Barbuda and St Vincent and the Grenadines have even submitted the candidacy of Maria Fernanda Espinosa, ex Foreign Minister of Ecuador. Thus, we have now an unprecedented scenario: two candidates for the General Secretariat who do not have the support of their own countries. Another candidate, Ambassador Hugo de Zela, does have the endorsement of his country, Peru.

7. The Lima Group, the top 14 countries in the hemisphere (not including the US), was established in 2017 under Peru’s leadership, to seek, outside the OAS, a negotiated solution to the Venezuelan crisis. The rationale behind this move: ideological polarization in the organization prevents an effective collective action; and the perception that Almagro’s combative stands towards Maduro precludes the organization from being an impartial intermediary or facilitator of an eventual negotiation process.

8. With the same logic, the Permanent Council formed a Working Group on the situation in Nicaragua, whose purpose is to facilitate negotiation between the government and the opposition. Significantly, the new mechanism allows the opposition’s voice to be heard, unusual for an inter-governmental organization where one hears only the voice of the representative of the executive branch.

Thus, in their assessment of the candidates for the General Secretariat, Member States would have to consider which of them represents the best option to manage an organization that in recent years has undergone significant changes in its nature.