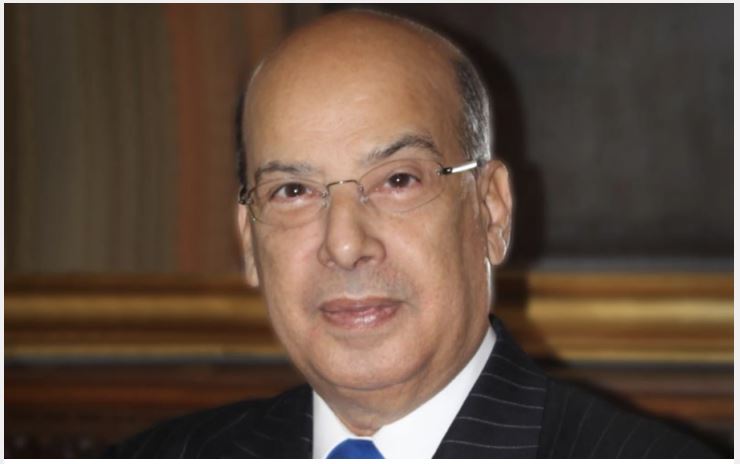

The following is a section of the Editorial in the December 2019 edition of: The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs. The Editorial was written by award-winning African journalist and publisher, Kayode Soyinka.

That could be seen in Rwanda’s confidence in branding this as ‘Africa’s CHOGM’. And why not? Africans have that family spirit of doing things together and leveraging on the success of a fellow African nation.

Besides, CHOGM does not come to Africa as frequently as it should. After South Africa in 1999, Nigeria in 2001, and Uganda in 2007 there has been a 13-year gap for the continent, and, of course, many African leaders were displeased by the way that Patricia Scotland got elected as Secretary-General of the Commonwealth in Malta in 2015.

But the truth be told, Africans only have themselves to blame for the choice of Baroness Scotland by putting forward a candidate of their own for whom, eventually, they could not get enough support, and at a time when it was the widely held view in Commonwealth circles that it was the turn of the Caribbean, not Africa, to produce a S-G.

Elections were conducted in Malta in November 2015 by Commonwealth Heads of Government or their representatives to fill the post at the expiry of the term of office of Kamalesh Sharma from India.

The popular Caribbean candidate who had the endorsement of 10 of the 12 Commonwealth Caribbean countries was Sir Ronald Sanders. The British government however wanted a S-G over whom they could exercise influence, particularly as they were concerned about the successor to Queen Elizabeth as Head of the Commonwealth.

They desperately wanted Prince Charles to succeed his mother. Had the headship shifted away from the British Monarchy, it would have been a blow to the pride of the British Government. Therefore, the British Government persuaded the Government of Dominica to act as a surrogate for Britain in nominating Baroness Scotland, a member of the British House of Lords and a former Attorney-General of Britain, who had been born in Dominica but left for Britain when she was two years old.

In addition to wanting to influence the incoming S-G over the headship of the Commonwealth, the British Government also wanted to retain their influence over the agenda of the Commonwealth, having experienced S-Gs who had asserted the independence of the Secretariat from Whitehall and favouring direction from a broader range of Commonwealth leaders.

Sanders had received firm indications of support from African governments, including the Presidents of Nigeria, South Africa, Kenya and Tanzania. But, Mmasekgoa Masire-Mwamba of Botswana who had served as Deputy Secretary-General at the Commonwealth Secretariat decided to run for the post, even though it was not Africa’s turn – a point that even many African governments had accepted.

However, their efforts failed to persuade Botswana not to persist with its candidate, even though they emphasised that this would break solidarity with the Caribbean and probably rupture the strong co-operation between the two regions.

The Botswana candidate won greater support from African countries at the last minute, largely because Nkosazana Clarice Dlamini-Zuma, the South African Foreign Minister, was Chair of the African Union Commission.

In the absence of President Jacob Zuma, who had personally pledged his support for Sanders, she persuaded some African Foreign Ministers to stand behind an African candidate, particularly a woman. She was joined in this last ditch effort by Amina Chawahir Mohamed Jibril, Secretary for Foreign Affairs of Kenya, whose President Uhuru Kenyatta also did not attend the Conference and who had personally given Sanders his support.

In the meantime, the British had marshalled the support of the ‘old’ Commonwealth countries behind its ‘Caribbean’ candidate, Baroness Scotland. Prime Minister David Cameron was especially active, describing the Baroness to Justin Trudeau, who was elected Prime Minister of Canada on the eve of the 2015 Malta CHOGM, as ‘one of us’. Australia was also particularly active in pressuring Pacific countries to back Scotland.

At the Malta vote, Sanders polled the lowest number of votes, largely because his African supporters dwindled as a result of some key heads of government not attending the meeting, and the Pacific countries bowed to pressure from Australia.

On the second run-off, several votes were deliberately spoiled by Heads of Government who supported neither of the two candidates, but Caribbean countries that had supported Sanders decided to cast their votes for the other nominal Caribbean candidate.

Only one vote separated the two when the tally was taken, including several spoilt votes. Botswana called for a third vote, but the Conference Chair, the Prime Minister of Malta, and an EU colleague of David Cameron (the Brexit referendum had not yet been held), ruled the contest over.

By not supporting Sanders, the Africans allowed the British to take control of the Secretariat. It is only the Baroness’s alleged excesses in the post and her below-par performance that have now caused them to be concerned about her remaining in office. The ‘old’ Commonwealth that brought her in is now in the forefront of wanting to remove her – the person they described as ‘one of us’.

It will be unprecedented if Baroness Scotland’s tenure is not renewed and she is removed from office when the Heads of Government meet in Rwanda. However, if that should happen and Africa covets the post this time round, they will have to make amends to the Caribbean for failing to support that region and its favoured candidate Sanders in 2015.

And if that should happen, this could truly be ‘Africa’s CHOGM’ that members will remember for a very long time – just like Abuja in 2001 when President Robert Mugabe sensationally pulled Zimbabwe out of the Commonwealth. And this will undoubtedly be an added boost, again, for Rwanda’s international status with President Kagame, who until recently was Chair of the AU, a Rwandan also as S-G of the Francophonie, and a Kigali CHOGM to be followed by two years of Rwanda in the chair of the Commonwealth.